back to articles

back to articles

Artistic endeavor is boundless in its potentialities. This almost self-evident assumption is brilliantly proven by the history of art and literature. But the question is boundlessness of what and which potentialities «Of from»-the answer is «yes». Of sense?-and again we agree. However, boundlessness of form and sense does not at all imply that the utmost bounds of artistic creation demonstrate that a certain regularity, cyclic recurrence and even reiteration are inherent in formal qualities of works of art and literature. That is why the problem of prototype and copy in particular is so widespread. What about meaning? It is multi-variant as well and amenable to estimating and regulating. Remember V. Pronp’s “Morphology of the fairy tale” and everything will become clear.

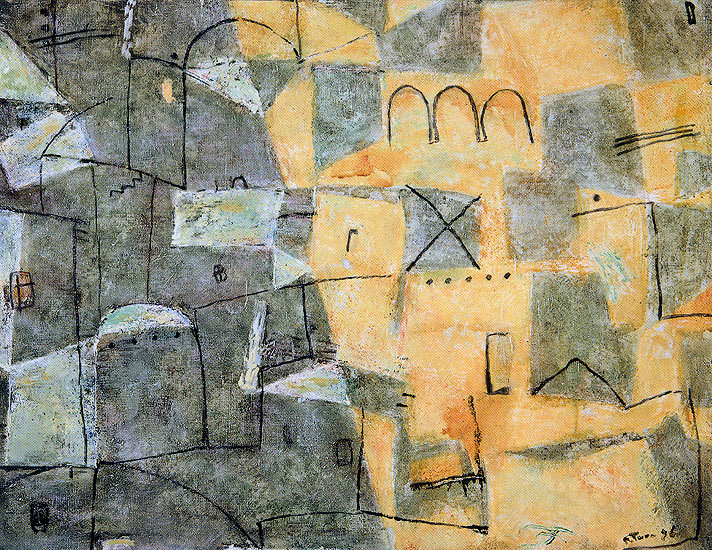

Rustam Turaev’s belongs to the layer of creative experience where the meaning of the original sense and the corresponding forms actually lead to the boundlessness of available state of sense- and form-formation. These are the state, sense and form of the artist’s paintings we are going to peak about. In other words, we shall be dialing with the poetics of the artist’s works, his original and topical ways of expression of sense and form directed beyond the bounds of narrative and vectorial time flow.

One of the most difficult and crucial element of the creative process is giving a name to a painting (sculpture, story, poem or novel). To give the right name to something or somebody is extremely difficult, as the name the name should be commensurate with the inner nature of the one to be named. It is not at all for nothing that in religious life of the past and present the name is given by a priest or clergyman, i.e. by a person who has accepted the whole responsibility for the inner essence of the person he is giving the name to.

As for Rustam Turaev’s works, the names of his paintings do not define the motifs, which are not to found in most of his works. For him the name of the painting is a designation of a notion and, as a rule, the shortest description of an abstract and timeless situation.

Here are the examples. The painting “Outskirts” (1993). The outskirts of what? The outskirts where? There is no answer. It is something and somewhere the artist called “outskirts” (of a town, country, state, land). “The old park” (1997). There’s an empty bench among leafage less trees. Who is it for? The one, who once sat on it, has left, while the one who is going to take this place has not come yet. This is a situation of timelessness, which is so typical of the artist’s works. He loves, is fond of and persistently obsessed by the idea of bringing out timeless and even crucial situations.

“Important meeting” (1998) - who with? At what time? Where exactly? - This is not really important. The characters are designated only to describe the named situation, the situation which is crucial as the past and the future change over each other under the strained and prolonged silence of the present.

Rustam Turaev is fond of the world of dreams, the world of non-obvious meanings and unfinished situations

The state of affairs is getting more acute when the painting’ name itself (and only that of the situation) becomes not only a name, but an organic part of the depiction. “A little cherry” (1998), “Dandelion” (1996), “A drop” (1997)-all these common nouns together with the paintings are metaphors. They are not a symbolic allusion, but a metaphorical description of some qualities of a depicted or imaginary model. In such cases the artist considers the name to be one of the significant signs of the depiction.

The artist’s favorite metaphor and depiction of crucial and timeless situations of spatial and temporal shift are the evidences of his tense and brittle view of the world.

But such is the course of the life of the artist himself. Rustam Turaev is a mixture of two bloods. He was born in Dushanbe, but now he lives in Nalchik; he studied in Leningrad, but his work was closely connected with Moscow; he also worked abroad. A man from Nowhere. This is how the Suthian masters (sheikhs) were called. Their immense spiritual and creative potential could not allow them to be delayed either in space or time for even a moment. Their abode was the city of Nowhere (Naokudgaobod). In the authorized and poetically molded biography, Rustam Turaev involuntarily enhances the impression being formed: wine, drugs, the threat to be shot. The threshold of sensible death is a definite meeting with timelessness. Those who have experienced the effect of drugs should clearly remember a sharp spatial and temporal shift of consciousness. The drug chronotone is much more real the real one, is much more actual than the actual one and there is much more entity init than in the realitie

The artist is sad, sad inside himself; he is excessively thoughtful, thus, being so much considerate towards things, not objects. When an object becomes the subject of thought, it turns into a conceivable thing. Motives of dreams and non-obvious sadness are not the object of depiction, but an organic part of the artist’s inner life. Some real characters (like a car or a turtle) are introduced and depicted near a sleeping man to demonstrate the inseparable connection between the world of dreams and the real world. The dream and reality are quietly neighboring with each other, or even so: the reality is always ready to transfer into the dream of a sleeping man – the reality is his dream.

Rustam Turaev is fond of the world of dreams, the world of non-obvious meanings and unfinished situations. He is fond of the world of stiff time. A girl is playing the flute – the time lasts in order to acquire and infinite continuum together with the sound. From the point of view of grammar, it is a depiction of the Present Continuous tense. Playing the flute (both longitudinal and diametrical) is important to the author due to the only purpose: he does not like and he overcomes the motif. His images are metaphorical: they carry the audience away towards the distance and the unknown like the sound of the flute. The visual series imperceptibly change over into audible ones, space transforms into time. Thus appears “The birth of the Sound” (1993).

In a case like this, the artistic devices employed by Rustam Turaev are not important as well. The heads of his characters are sometimes decorated with flowers and flower baskets. Of course, one may remember the closet analogies (or borrowings, as you wish): Tyshler, Abdusalomov. But the point is absolutely different. It is important to understand what for and for the shake of which goals these devices are being used. What is important is the situation together with the time-proven devices introduced by the artist. “Alone” (1995) is a beautiful and simple composition. There is no motif, but the meaning is disclosed through allegory: the shroud covering a figure undoubtedly reproduces the shape of a minaret. A man hidden in the minaret is a metaphor of timelessness, as the minaret is designed to proclaim eternal, divine and boundless Word.

Rustam Turaev like the sense of rhythm reproduced by the movement of a painting. The painting is not covered; it is a naked painting, poetically echoing the favorite naked models and the whole world of senses. The colored spots used by the artist cannot stop the movement of the painting; they are called for something else. Depending on brightness and tone of the colored spots they solve a psychological problem by evoking certain feelings in the audience. For an artist of such standing it is not the presence of a colored spot, which is important, but the strain of the neighboring spots. Thus appears the coloring, the single palette of the colors typical of the most paintings by Rustam Turaev.

There is nothing from the Orient in the artist’s works. There was no genre settles a lot. The artist could not help remembering the East. Turaev’s eastern disposition displays through the meaning and poetic style of his works.

Institute of Oriental Studies Russian Academy of Sciences